Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones on Preparing for Death — by Rev Iain Murray

I am very grateful to two very old and dear friends of my family.

Firstly, to Iain Murray for agreeing to the publication of his address, which as far as I know has never been published before, though some elements of it are in his biography of the Doctor. Below is the transcription of a talk Iain gave to a ministers fraternal in 1982, shortly after Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones went to glory. I am, secondly, also grateful to Ann Winch for suggesting the idea of this article and for transcribing the tapes. The words in italics below are where particular stress and emphasis were placed by Iain in the original recording.

Many of the readers of this article will be familiar with Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones, one of the most influential evangelical preachers and writers of the C20th, but for those who may not be, I attach a short biographical note at the end.

How strange in Gods’ providence and how timely that in the month in which, more than any other over the last 75 years, we have been inescapably thinking as a world about death, that this article should emerge and be published. It is about a vital topic for all, Christian or not: preparing for death.

May God use this powerful talk to enable us all to prepare for death and meeting God. I can best sum the message up in a quote from Dr Lloyd-Jones in the passage below:–

The Christian is not afraid of death because he has the assurance that he will not be left alone. . . Death is not parting only but more, it is meeting and though it is an experience we have never passed through we have the assurance that nothing can separate us from the love of Christ and that at death we will meet with him.

Many are now understandably afraid of dying of Coronavirus on their own: but friends we have this mighty assurance from the Lord Jesus himself that if we are his, we will never be left alone.

* * *

His [Dr Lloyd-Jones’s] Ministry ended abruptly at the beginning of March 1968. He was seriously ill and had a major operation. He wonderfully recovered from that operation, and returned to the Westminster fraternal the following October and gave an address on preaching. God had restored him and he was full of his old vigour.

It was only in the Summer of 1979 that there were signs of his health failing. He was unable to go to his beloved Ministers’ Conference in Bala that Summer. Neither could he go to the Westminster Conference later in the year. In the November of 1979 he said that he was conscious of getting old, and there were symptoms that his health was not good. I saw him in November 1979 and key things stand out about that meeting. The first was that he hoped to go to a clinic in Florida for treatment, as he realized his health was deteriorating. He had not been in the States since 1969 and had not expected to go again but he had heard of the good work being done in a particular clinic and hoped to go around December 1979. As he spoke about that proposed visit, it was reminiscent of the words in Daniel 3 (though he had not consciously applied this text) as Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego were facing death: ‘Our God whom we serve is able to deliver us from the burning fiery furnace, but if not we will not serve thy gods.’ Lloyd-Jones said ‘I hope to go and derive benefit from the treatment and carry on as before, but if not I shall do what I can.’

But as it turned out, he was not well enough to go and never crossed the Atlantic again, but he was perfectly satisfied with either alternative. I did not see him personally until 1980, and by that time there was a very apparent change in him. He was obviously weak, had lost a great deal of weight. He sat quietly in his chair in his room at home at Ealing (London), but when he began conversation that day he was more fervent than I had seen him for a long time. I don’t think I was ever more moved than at the conversation we had that day in March 1980. He was not speaking of possible treatment or recovery but the subject that was largest in his conversation was Preparation for God — that was his subject.

And he began with referring to some words by the famous Doctor Thomas Chalmers. He had said that it was greatly to be desired that before death that Christians have time to prepare. . . time to disengage themselves, time to withdraw from the busyness. . . that so occupies them, and that if we live three score years and ten, and if we reach the seventh decade, that decade should be like a Sabbath — a preparation for heaven.

Then the Doctor (Lloyd-Jones) said ‘I agree with Chalmers absolutely. We don’t give enough time to death and to going on — it is a very strange thing this. Death is the one certainty, and yet we don’t think about it. We are too busy. We just allow life and circumstances so to occupy us but we don’t stop and think. I am grateful to God that I have been given this time. People say about sudden death that it is a wonderful way to go, but I have come to the conclusion that that is quite wrong. I think the way we go out of this world is very important. The hope of sudden death is based upon the fear of death. It is the hope of wanting to slip through death rather than to face it.’

Brethren, I wish you could have heard him speak on those words. Death, he said, ‘should be faced victoriously.’ Then he said ‘I am grateful therefore for this experience, and maybe my present trouble is to give me this insight. My great desire now is therefore that I might be able perhaps to bear a greater testimony than ever before’ (meaning in the face of death). He wanted to face death with Christian testimony. In the course of this conversation, I mentioned a Christian who had died gloriously but who had lived rather feebly, and I said to the Doctor, wouldn’t it have been a great thing if he had lived as he had died? I got a mild rebuke! He was not impressed with that statement because he detected something in it. He said, ‘Don’t underestimate dying — death is the last enemy. (He repeated this twice). Men may live well who do not die victoriously — whereas to die gloriously is a great thing. It is idiotic that men do not prepare to die.’ He then referred to George Whitefield‘s conversation with one of the Tennant brothers in New Jersey when, even though he was still in his twenties said he was ‘ready to go.’ There was much more said, but above all he was full of thankfulness for having been given time to prepare to die.

When I left him on that day in March 1980, I scarcely knew whether I would see him again, I hardly thought that it was possible unless I made haste. However not only did a few of us see him again, but we saw him in the pulpit again. Those who heard him in Glasgow will not forget it! — from the 2nd Psalm. . . and filled with tremendous earnestness and passion on the words ‘Kiss the Son lest he be angry. . .’ That sermon is on tape, and after that sermon I saw him do something that I never saw him do before — he had to sit on the pulpit steps — it was quite amazing that he was there. I believe he had gone to encourage the many younger ministers who were there. Then he went by car to preach in Wales on the Sunday evening. And so from June 1980, his public work was really finished. He attended the last fraternal in a venue in London later in the year. He was not seen in public after that. He was at home in Ealing and also at his son-in-law’s in Cambridge a little while, where he took a walk or two, but that was the end of being away from home (Ealing). He was at home in Ealing, apart from a few brief visits to hospital. He was never confined to bed. To the end of his life, except for one exception which I will refer to soon, he had all his faculties. His memory was in full strength until the end — a wonderful thing and a great blessing. He didn’t spend a day in bed. He sat in his chair quietly in his room.

I saw him then in July of 1980. When I arrived in his room he had a text. It was a text for me, and a text he had obviously been preaching to himself: ‘And the 70 returned again with joy saying “Even the devils are subject unto us through Thy name.” In this (said our Lord) rejoice not, but rather rejoice because your names are written in heaven.’ The lesson of the text, he said, is that if we are living upon what we do, if our happiness is based upon our preaching or our service for Christ, there is something deeply wrong with it. ‘Not in this,’ says our Lord, ‘but rejoice that your names are written in heaven.’ The ultimate test of a preacher is what he feels like when he cannot preach. It is a real snare for the preacher to live upon preaching. People say to me now ‘It must be very sad for you not to be able to preach.’ ‘Not at all,’ he would reply ‘I was not living upon preaching. I can and do rejoice.’ It was a great privilege to hear him say that. He went on to say that though he could no longer preach, God was helping him to pray. It was moving to know how many of you brethren he was praying for — some of you know you were in his prayers, others of you don’t know — a great number of men in the ministry of the Gospel. He was rejoicing in the quietness that God had given him, with more time to pray and he was not downcast that he was not preaching.

At that same time in July 1980 he spoke again about dying. He said ‘We could face it like this. First, we all have to die — that is a fact, it is common sense. But where does Christianity come in? The Christian is not afraid of death because he has the assurance that he will not be left alone. Then he focused on the parable of Dives and Lazarus, and focused particularly on the verse, ‘And the beggar died and was carried by the angels into Abraham’s bosom. The angels (he said) came! I believe in the ministry of angels and think of it more and more. Death is not parting only but more, it is meeting and though it is an experience we have never passed through, we have the assurance that nothing can separate us from the love of Christ, and that at death we will meet with him.’

He spoke of an old man at his first congregation at Sandfields, and the Doctor was at his death-bed, and the man was at the extremity of life and suddenly he threw up his arms and his face shone, and he was already meeting the Lord before he had gone. The Doctor spoke of the reality of that: ‘We are going to be with Christ.’ ‘Our greatest trouble is that we really don’t believe the Bible. . . exactly what it says — exceeding great and precious promises. We think we know it, but we do not really appropriate this and actually believe it is true. Here we have no continuing city. Our light affliction that is but for a moment. We have to take these statements literally. They are facts, they are not merely ideas.’ Then he said, as it were, not merely to me, but to all of us. ‘This is what I feel — you people have got to emphasize it more and more.’

In October I saw him again in his home. There was a further change in his health. He was sitting still in his chair as he was in July, but this time he wasn’t rising to his feet. He was patently weaker, and on that day in October, he was full of the subject of the wonder of the grace of God, and more than once the hymn ‘My hope is built on nothing less than Jesus’ blood and righteousness. I dare not trust the sweetest frame, but wholly lean on Jesus’ name’ and the next verse that ‘His covenant, his blood support me in the whelming flood. When all around my soul gives way he then is all my hope and stay.’

He referred to the words of old Daniel Rowland at his death ‘A poor old sinner saved by grace’, and much more of similar vein. By January of 1981 — of this year — the thing that struck me in meeting him in January, was the extraordinary seriousness which characterised him. People said that the Doctor didn’t laugh much, and I suppose that’s true, but he smiled a great deal didn’t he? But you know, I never knew him smile as much as towards the end of his life, when he’d lost so very much weight and was very thin and emaciated towards the end, and his smiles were more and more pronounced and his face (without exaggeration) often seemed to glisten. He was desperately serious.

Then at the beginning of February I saw him twice again, and that was the last conversation I had with him face to face. I spoke to him on the phone after that, but not face to face. He was quite evidently going down and he knew that — he simply did not know how long it would be. But throughout February, he was moving around until the last week. At the beginning of the last week of the month, it became clear that he was losing the power to speak. He didn’t suddenly lose it, but gradually his breath went.

One of the last times he spoke was this: His consultant had come to see him — a Christian man who used to attend Westminster Chapel. The consultant was speaking with him but Lloyd Jones was not talking, but he could say a great deal, as you know, by nodding his head and by his look. The consultant said that he wanted to give him some antibiotics. The Doctor just shook his head. ‘Well,’ said the consultant. ‘When the Lord’s time comes, even though I fill you up to the top of your head with antibiotics, it won’t make any difference.’ The Doctor still shook his head. ‘I want to make you more comfortable,’ the consultant said. The Doctor said nothing, but shook his head. The consultant replied, ‘You know it grieves me to see you sitting here weary and worn and sad.’

That was too much! ‘Not sad!’ the Doctor said! It must have been one of the last things he said. Throughout the rest of that week, he gradually lost all power of speech. And yet, without speaking, he was in full communication by smiles, by gestures — it’s hard to describe, but he spoke with his face, and I’m sure there was not a moment when there was not communication. Sometimes, of course, he wrote on a bit of paper. On the Thursday, he wrote to Mrs. Lloyd-Jones and her daughter ‘Don’t pray for healing. Don’t hold me back from the glory.’ It’s hard to read that note. Those that knew his handwriting often found it hard to read! But this was particularly hard — except for the word glory. That stood out in the sentence.

Friday of that week, he was meeting with a few people — he was full of smiles. On Saturday he was lower — semi-conscious for several hours of the day — and then by late in the evening on Saturday, it was evident to Mrs Lloyd-Jones he was unconscious. He was still sitting in his chair in his usual place, but he was unconscious. Now, it is a very wonderful thing that Mrs. Lloyd-Jones, right to the end, had been able to get him up in the morning — help to dress him — no one else was needed until that one evening of his life, as it proved to be — there was no way she could get him to bed. He was unconscious, sitting quietly just there in his chair. So Mrs. Lloyd-Jones and her daughter determined to ring the Ambulance people. They came quite quickly, and in God’s goodness they were wonderfully kind, carried him to the bedroom, undressed him, and put him to bed in perfect ease and quietness and comfort, and after he had been in bed for just a short time and Mrs. Lloyd-Jones had gone out, he came round and his daughter Anne was there and at once he knew exactly what was happening, but he was obviously looking for Mrs. Lloyd-Jones round the room — she wasn’t there. And then she came in and asked him if he would like a cup of tea and he nodded, and he drank half a cup of tea and they had a beautiful half hour with him and quietly he went to sleep. And that’s how he went home. Mrs. Lloyd-Jones woke up beside him in the morning and he had gone.

That text in Psalm 37 is so appropriate — it was an abundant calm and peace.

I [Iain Murray] want to draw out a few things. Some of the reading he got through in his lifetime was wonderful, but to the end he was reading! It’s a great rebuke to us. The aged Apostle Paul in his prison, requested the cloak to be brought which he had left at Troas — and especially the parchments. The Doctor was like that, he really loved to read, right to the end. He read McCheyne’s division of Bible every day — he had done that since the beginning of the 1930’s. The reading on that last day — Saturday in February — 1 Corinthians 15 was the last passage open on his knee. He believed every minister should read through the whole Bible at least once a year. He read morning, noon, and night. If he could go on exhorting us, he would exhort us to let nothing interfere with our reading. To feed the souls of men we must ourselves be prepared and cut off things that would prevent our doing this.

The theme that he spoke of so very frequently was the wonder to him of the guiding hand of God — the Providence of God. I don’t think he spoke on anything more than that — the way God intervenes and the way God does things that he [Lloyd-Jones] never for a moment imagined. . . At 24, he was smitten with conviction of sin and began to discover that he had never been a Christian at all. He wrote at that time, ‘I shudder when I realise how unworthy I am — how ignorant of the dark hidden recesses of my soul, where all that is devilish and hideous reigns supreme.’ Then, by 1925, rejoicing in the wonder of the Gospel. Then, irresistibly, he was compelled to enter the work of the Ministry (leaving his medical career). He would wish to impress upon us all that we must also always know and believe God’s hand is day by day upon his people. He is concerned for us. ‘Be careful for nothing’ was a text he quoted very often, ‘Be anxious for nothing — God’s faithfulness, God’s love, they are invincible. We have no business to be dismayed.’ He took a long-term view of things: ‘We mustn’t get disturbed, alarmed at what’s happening at the moment. All is in God’s hands, he reigns. We can be peaceful and commit all to him.’ He said that after he had gone, God would care for his ministers: God was in control.

Biographical Note

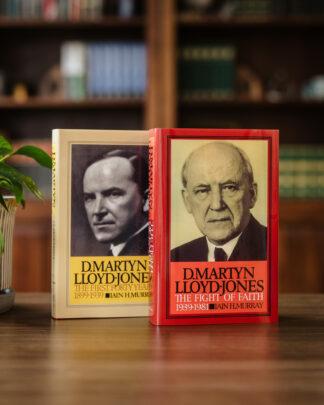

Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones was born in 1899, just a few days before the turn of the C19th into the 20th. Born and raised in Wales, he trained as a medical doctor and achieved notable success in his profession before responding to God’s call to enter the Christian ministry. First in Wales at Aberavon (Port Talbot) and then from 1939 at Westminster Chapel in London, his powerful biblical preaching, ‘Logic on Fire‘, converted and influenced tens of thousands. His books and recorded sermons since his death have continued to have a enormous impact. Through him and others under God, there came in the second half of the c20th a wonderful worldwide revival in Reformed preaching and literature, the latter notably initiated through the Banner of Truth Trust. Dr Lloyd-Jones died on St David’s Day (1st March) 1981 and was buried at Newcastle Emlyn, near Cardigan, Wales. I, and thousands of others, attended a moving memorial service at the Chapel the next month. If you would like to find out more about Lloyd-Jones, the best place is the two volume biography published by the Banner of Truth and written by Rev Iain Murray. Iain Murray co-founded the Banner of Truth Trust and was the assistant minister to Lloyd-Jones at Westminster Chapel.

This article was first published on God, Gold, and Generals, the blog of Jeremy Marshall, and has been reproduced by kind permission.

More on Lloyd-Jones

D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones

2 Volume Set

Description

I am very grateful to two very old and dear friends of my family. Firstly, to Iain Murray for agreeing to the publication of his address, which as far as I know has never been published before, though some elements of it are in his biography of the Doctor. Below is the transcription of a […]

Saved By Grace Alone

Sermons on Ezekiel 36:16-36

Description

I am very grateful to two very old and dear friends of my family. Firstly, to Iain Murray for agreeing to the publication of his address, which as far as I know has never been published before, though some elements of it are in his biography of the Doctor. Below is the transcription of a […]

Latest Articles

On the Trail of the Covenanters February 12, 2026

The first two episodes of The Covenanter Story are now available. In an article that first appeared in the February edition of the Banner magazine, Joshua Kellard relates why the witness of the Scottish Covenanters is worthy of the earnest attention of evangelical Christians today. In late November of last year, on the hills above […]

A Martyr’s Last Letter to His Wife February 11, 2026

In the first video of The Covenanter Story, which releases tomorrow, we tell the story of James Guthrie, the first great martyr of the Covenant. On June 1, the day he was executed for high treason, he coursed the following farewell letter to his wife: “My heart,— Being within a few hours to lay down […]