Old Princeton (2)

This is the second part of the 2012 Annual Lecture of the Evangelical Library in London. The first part can be found here. The lecture for 2013 is to be given on Monday June 3rd at 6.30 pm at the Evangelical Library and the subject is ‘The Doctrines of Grace in an Unexpected Place: 19th Century Brethren Soteriology.’ The Lecturer is Mark Stevenson, USA.

Old Princeton Theology

What then was the theology of Old Princeton? In his inaugural address1 as Professor of Didactic and Polemic Theology in 1921, following the death of Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield, Casper Wistar Hodge said this,

The old theology (meaning Princeton’s theology) . . . is characterised by definiteness (I like that) . . . The distinctive mark of the old theology, then, is supernaturalism and the realisation of the infinitude and transcendence of God, in opposition to the paganism which finds God only in the world.

Hodge proceeds to highlight what he considered to be the three fundamental features that defined and shaped not only the theology of Old Princeton but of Reformed theology as a whole at its purest. These were the three things that he felt captured and characterised the essential heart of the old theology: pure theism, pure religion and pure grace or evangelicalism. Those were his three headings. I want to look at these three, defining and contouring the essential character of the theology of Old Princeton.

1. Pure theism

What is ‘theism’? Theism is the interpretation of the universe from the standpoint of God and his purpose. ‘Pure theism’ is, says Hodge, ‘just the construction of all that happens in the physical and mental spheres as the unfolding of the eternal purpose of God, and the refusal to limit God either by the world of nature or the human will’ (page 600). Think of Paul’s ‘all things’ in those great words found in Ephesians 1:10. Old Princeton resolutely resisted, almost through its whole life, the theological spirit of the age – which it almost always called the infidel spirit – that sought to merge God into ‘the world process’. From its inception Old Princeton taught and proclaimed God as ‘the Almighty Creator, Preserver and Governor of the universe, whose power and purpose are not limited’ (page 601). And the spirit of the age that Princeton was always engaging and seeking to refute continues to the present day. You get it in the theological expression known as ‘open theism’ but you get it everywhere – people who will not let God be God. Pure theism allows (if that is the right word) God to be God. The Princeton men were unashamed predestinarians.

2. Pure religion

By ‘pure religion’, Old Princeton meant absolute dependence on God and not the human will, ‘using God only as a helper in our struggle against the world’ (page 602). I was preaching last night on 1 Samuel 4 where the Philistines have defeated Israel and where the elders ask the right question ‘why has the LORD done this?’ but without seeking God, without repentance, they conclude that the ark will save them. ‘Let’s get the box’, they say, ‘it will save us from our enemies’. And how often the church resorts to ‘boxes’, ‘religious boxes’. I think evangelicals do that today. How do we engage with the world today? In dependence on God? No, we look to create brighter, lighter, cooler, more hip services. Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not advocating that we linger in the past. If there are good hymns that are modern to be sung, let’s sing them. But there is something fundamental here to confront. Do we really believe that God alone is our helper in our struggle against the world? If we did our churches would be praying with a different spirit – and I speak first to my own heart and my own congregation.

Hodge pleaded, ‘Take this attitude of pure religion; let it have its way in all your thought, in all your feeling, and in all your life, and you have taken just the position of the Reformed faith, and are in a position to defend yourself against naturalism in religion’ (page 601). God alone is our helper. ‘Once let this life-blood of pure religion flow from the heart to nourish the anaemic brain and work itself out in thought, and it will wash away many a cobweb spun by a dogmatic naturalism claiming to be modern, but in reality as old as Christianity itself (page 602). Pure religion – absolute dependence on God and not human will resources. Again, that is not Hodge yearning for the past. Rather, he is asking whether we really believe that God alone is our helper.

3. Pure grace

In a little more detail here. Old Princeton was marked by the unshakable conviction of the absolute dependence of the sinner upon God for salvation. I’ll never forget my daughter coming home from school one day and me asking how school had gone. Girls answer questions like that, boys don’t tend to. She said that the teacher had said to her ‘you’re a Christian’ and then had asked if she knew what a Calvinist was. (It must have been an English class or something like that.) She had answered ‘someone who believes that only God can save sinners’. My heart was moved by that answer. Thankfully that’s her conviction today 13 years later. Pure grace. Throughout its history Old Princeton battled against the theological and philosophical spirit of the age. Optimistic humanism was what lay at the heart of much of the thinking at that time – in literature, in scientific enquiry, in theology.

The same essentially optimistic humanism drove aspects of theology in the church, especially the ‘New School’ engine that was fiercely opposed by Hodge and his Old Princeton colleagues. They saw the New School theology of men like Nathaniel Taylor of Yale, as an expression of the conflict that had afflicted Christianity from the beginning, the conflict between those who sought to vindicate God’s sovereignty in salvation and those who ultimately sought to promote the ‘rights of man’. I think you see it widespread in American Christianity today – the democratisation of the church. The individualism that pervades American evangelicalism to our -and often their – embarrassment.

This accommodation to the spirit of the age – this taking from what is seen in the world and trying to use it to make the church acceptable – was seen in the New School attempt to ‘soften’ the biblical teaching on total depravity and moral inability. Against this ‘accommodation’, Princeton especially directed all its energies. Old Princeton was convinced that when the biblical truth of total depravity goes, God’s glory and sovereignty are diminished and ultimately denied.

When Charles Finney’s Lectures on Systematic Theology were published in 1846, Hodge wrote a damning review in the Biblical Repertory. For Hodge, Finney’s great error was to begin with philosophy and not with Scripture – in Finney’s doctrine of salvation ‘Christ and his cross are practically made of none effect’. And when Finney embraced a perfectionist doctrine of sanctification, Charles Hodge simply responded that no-one is perfect who is not perfectly like Christ. Sometimes the simplest statement is the most powerful. He continued, ‘Need any reader of the Bible be reminded that the consciousness of sin, of present corruption and unworthiness, is one of the most uniform features of the experience of God’s people as there recorded?’ Old Princeton passionately believed that only when we ascribe all the power in our salvation alone to God can he be truly glorified. The moment you ascribe an iota of dependence on human merit and human power for salvation, ‘You are in unstable equilibrium between the Reformed faith and a bald naturalism and Pelagianism in which this relentless philosophy has now entered the centre of your life and attacked the very ground of your hope for yourself and the world’ (page 601).

Old Princeton engaged with all its intellectual powers and spiritual energy in defending and promoting the ‘faith once for all delivered to the saints’. Men like Charles Hodge and B. B. Warfield were Christian scholars. They believed passionately in an educated ministry that would expound the glory of God’s saving, supernatural revelation and defend it against the enemies of the age, whoever they were. Two concomitants arose from that. Firstly, they opposed pietism. They promoted piety but they vigorously opposed pietism. Says Hodge, ‘We cannot withdraw into the citadel of our heart, and suppose that thereby we have saved the Christian religion’ (page 599). Secondly, they opposed an anti-intellectualism. Nor can we ‘set up an apologetic minimum and hope to defend it and escape with the essence of Christianity from the flood of this naturalistic (that is, non-supernatural) stream’ (page 599). And that is what so much of so-called Christian philosophy in the 19th century was about – really from Hegel to Schleiermacher. And many Christians were imbibing this understanding with a reductionist apologetic and reducing Christianity to feelings and experience.

C. W. Hodge heartily agreed:

Only by a bold assertion and adequate defence of . . . Christian supernaturalism can we maintain our common Christian faith: by the defence of a supernatural Bible as the Word of God, and a supernatural salvation which comes from the power of Almighty God (599).

I love that.

B. B. Warfield was once asked ‘What is Christianity?’ and he said, ‘unembarrassed supernaturalism’. Would to God that we today were as bold. Too often, I fear, we shrink back from so-called intellectual attacks. Let the dead bury their dead; you go and preach the gospel. We should be unintimidated by these attacks from right or left. We are unembarrassed supernaturalists. Why? Because supernaturalism has invaded our being; captured us, changed us. The gospel is the power of God to salvation. We have a supernatural Scripture and a supernatural salvation.

Let me say in this context that many good theological seminaries and colleges are in danger (or are already engulfed in the danger) of bowing to the ‘Academy’. It is one thing to engage with the Academy and another to seek its credibility – Princeton always did that and Warfield was held in very high regard by the German theologians – that should never be our interest! We need seminaries and colleges that live coram deo (before the face of God). In one sense, we do not care what the Academy thinks. I am not an anti-intellectual. I encourage people to use their minds, but do not be sucked into merely seeking the approbation of the Academy. What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?

So far we have said nothing about ‘the Five Points of Calvinism’. Old Princeton unashamedly taught the ‘Five Points’ – but not as doctrinal abstractions. Their Calvinistic soteriology was rooted within the Trinitarianism of Holy Scripture – the ‘Points’ were taught ‘proportionately’, within the setting of the full panoply of God’s redemptive revelation. Many years ago I had a sabbatical in Jackson, Mississippi. I was asked to complete certain examinations, including a viva, which I was happy to do. During the viva I was asked if I was a five point Calvinist. I replied that I found the question both demeaning to Calvin and to myself. Of course, I believe these things but too often we have abstracted the five points, as important as they are, forgetting their context. They become metallic and lack biblical proportionality. It is a little like taking five bones out of a body and admiring their symmetry. The great question in Calvinism is not, ‘How can I be saved?’ but ‘How shall God be glorified?’. Listen to Warfield, perhaps the greatest of Old Princeton’s teachers:

It is the contemplation of God and zeal for his honour which in it draws out the emotions and absorbs endeavour; and the end of human as of all other existence, of salvation as of all other attainments, is to it the glory of the Lord of all . . . It begins, it centres, it ends with the vision of God in his glory: and it sets itself before all things to render to God his rights in every sphere of life. From him and to him and through him are all things. To God be the glory.2

Caspar Wistar Hodge concludes his inaugural address with this, and here we will conclude too:

What other hope have we than that which this Reformed faith gives us? The forces of evil are powerful in the world today . . . In the realm of religious thought sinister shapes arise before us, threatening our most sacred possessions. And if we look within our own hearts, often we find there treachery . . . From foes on every hand around us and within; with dark clouds of yet unknown potency for harm forming on the horizon; we dare not put our trust in human help or in human will, but only in the grace and power of God (page 602).

This was the quintessential pulse beat of Old Princeton. Please God it may be so once again in our day. Amen.

Notes

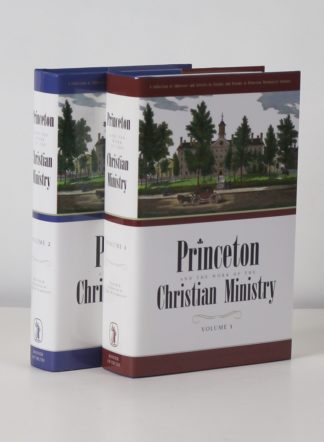

Princeton and the Work of the Christian Ministry

2 Volume Set: A Collection of Addresses and Articles by Faculty and Friends of Princeton Theological Seminary

price £34.00Description

This is the second part of the 2012 Annual Lecture of the Evangelical Library in London. The first part can be found here. The lecture for 2013 is to be given on Monday June 3rd at 6.30 pm at the Evangelical Library and the subject is ‘The Doctrines of Grace in an Unexpected Place: 19th […]

- B.B. Warfield, Works, Volume 5, p.358.

Ian Hamilton is the pastor of Cambridge Presbyterian Church.

Latest Articles

Finished!: A Message for Easter 28 March 2024

Think about someone being selected and sent to do an especially difficult job. Some major crisis has arisen, or some massive problem needs to be tackled, and it requires the knowledge, the experience, the skill-set, the leadership that they so remarkably possess. It was like that with Jesus. Entrusted to him by God the Father […]

Every Christian a Publisher! 27 February 2024

The following article appeared in Issue 291 of the Banner Magazine, dated December 1987. ‘The Lord gave the word; great was the company of those that published it’ (Psalm 68.11) THE NEED FOR TRUTH I would like to speak to you today about the importance of the use of literature in the church, for evangelism, […]