Richard Cameron: The Lion of the Covenant

The following is excerpted from Jock Purves’s Fair Sunshine: Character Studies of the Scottish Covenanters.

Richard Cameron (1648? – 1680)

Cameron of the Covenant stood

And prayed the battle prayer;

Then with his brother side by side

Took up the Cross of Christ and died

Upon the Moss of Ayr.

Henry Inglis,

Hackston of Rathillet

Sanquhar Town, 12 June 1680. A band of about twenty horsemen are clattering up the High Street to the Town Cross. People are running to see them. ‘It’s Richie!’ they cry, ‘it’s Richie Cameron! Here are the Hillmen!’ It is Richard Cameron, Lion of the Covenant, a Richard Coeur-de-Lion, indeed, with some of the faithful remnant. He and his brother Michael dismount. The others form a circle about them. It is the first anniversary of the Bothwell Brig slaughter, and for the murder of their comrades, this is their answer—the inestimably brave Sanquhar Declaration. In clear and solemn tones, Michael Cameron reads that they ‘disown Charles Stuart, who hath been reigning, or rather tyrannizing, as we may say, on the throne of Britain these years bygone, as having any right, title to, or interest in, the said crown of Scotland for Government, as forfeited several years since by his perjury and breach of covenant both to God and His Kirk, and usurpation of His Crown and Royal Prerogatives therein . . . As also we, being under the standard of our Lord Jesus Christ, Captain of Salvation, do declare a war with such a tyrant and usurper, and all the men of his practices, as enemies to our Lord Jesus Christ, and His Cause and Covenants, and against all such as have strengthened him . . . As also we disown, and, by this, resent the reception of the Duke of York, that professed Papist, as repugnant to our principles and vows to the Most High God.’ That high-born wretch, the Duke of York, had sneeringly threatened to make parts of Scotland like a hunting field. From the hunted, who knew him as ‘the devil’s lieutenant’, this was the answer. Thomas Campbell nailed up the fearless words. Another prayer, a verse or two of a Psalm, and those men of forfeited lives disappeared among their welcoming hills. Eight years later, the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and the Commons of England, with the Estates of Scotland, flung out King James Stuart, and put William and Mary upon the British throne. It was but a following of the brave, resolute few of the Sanquhar Declaration. As Carlyle has it, ‘How many earnest rugged Cromwells, Knoxes, poor peasant Covenanters wrestling, battling for very life, in rough miry places, have to struggle, and suffer, and fall, greatly censured, bemired, before a beautiful Revolution of Eighty-Eight can step over them in official pumps and silk stockings with universal three times three!’ Richard Cameron truly prophesied, ‘Ours is a standard which shall overthrow the Throne of Britain.’ It did.

* * *

To-day Northern Ireland is probably the most evangelically Christian part of Britain. This is the work of God. Had the south of the island known the gracious change experienced by the rest of Britain at the glorious Reformation, the history of our nation, religiously, socially and politically, would have been vastly different, and all for the better. It does not carry the light of the Reformation, the light of the gospel. But Ulster is part of God’s answer. And Ulster is a Covenanting triumph, and it was right that the last crushing blows against Stuart Romanism should be struck by Covenanter and Puritan at Londonderry, Enniskillen and the Boyne. It was in Ulster that Covenanters with Puritans settled in their godly thousands, and moved, as they termed it, ‘from one bloody land to another’. The ‘No Surrender’ of Derry is the echo of the Covenanter cry, ‘The Lord our Righteousness.’ And so the blessing of God on the generations has lasted through the centuries, and is there to-day. It is not political partition only that is in Ireland. It is a fundamental partition. It is that between people and people, between the open Bible and pure evangelical faith, and a power that would draw back again into a dense darkness from which there has been a merciful deliverance. But there are two great dangers in Ulster as elsewhere in this country. These are mere nominal Protestantism and Modernism. May the people so blessedly placed inherit their heritage, winning Christ! The present compilers of the Scottish National Dictionary have not forgotten Ulster either, and say, ‘The Scottish National Dictionary deals with the vocabulary of literary and spoken Scots, including the dialects of the mainland, Orkney, Shetland and Ulster from 1700 to the present day.’ Ulster is a British Covenanting triumph, and God’s blessing still is there. May the people speaking the language of their fathers, speak it in the Grace of God, as their fathers most clearly did. The United States of America, too, is a great result of the further development of the Reformation in the orderings of the Most High. It might have been settled by Spanish or Portuguese, and therefore, now been as South America, Romish, backward and dark. But in genius and constitution, in its strong depths and on its grand heights, it is a Protestant land. This is because of a people, such a people, in moral and spiritual stature incomparable, the finest expositors of Scripture ever known, the English Puritans. Carrying banished men and women, with their little children, the Mayflower was an earnest of a summer of spiritual bloom to be followed by a great harvest. The people of God suffer but to reign. Through going the way of the cross there was for them a fulfilment of the promise of the love and grace of God. And so these blood-brothers of the Covenanters went out and founded a nation like their own—lands of free men, lands of the gospel of the grace of Christ from which to other races the message of the redeeming love of God has been taken forth unceasingly. It was King Charles Stuart that caused these people to go, but God meant it unto good. Other ships were making ready to sail, but Charles of Divine Right imperiously forbade their going. Had he but known he would have had them go, and that quickly, for two of the names of the would-be Pilgrim Colonists were Oliver Cromwell and John Hampden! Oh those days of seeming calamity to those brave and noble hearts! Those were days of the planting of the Lord. The British Commonwealth and the United States of America owe much to sufferers for His Name’s sake, enduring and achieving by faith.

* * *

Alan Cameron, believing merchant in Falkland, Fife, had three sons of whom Richard was the eldest. The other two, Michael and Alexander, were also believers, and followed the Covenanting banner of blue. The only daughter, Marion, was a sincere Christian woman who died at the hands of violent dragoons. After his university days, Richard Cameron was a schoolmaster, but he knew not the Saviour. Sometimes he listened to the here-on-earth-to-day and there-in-heaven-to-morrow field preachers, and one day, obtaining mercy and finding grace, listened unto life. His own voice was soon heard among theirs, as of a trumpet clear and certain, and thousands listened to him. He was white-hot himself and had little use for the lukewarm. By his sincere example he inspired many. Even in the cold shadow of the gallows, just before they went into his Presence, there were those who testified to the blessing of God by him. But flat, haven-affording Holland soon had to receive him, and from that easy vantage point along with other exiles he often looked back with loving longing on ‘the land of blood’. While abroad godly hands were laid on his head, and he was set apart to the work to which he was surely called—the ministry of the gospel. After Brown, and Koelman, a Dutch minister, had lifted their hands, the great McWard kept his upon Cameron’s light brown locks saying, ‘Here is the head of a faithful minister and servant of Jesus Christ who shall lose the same for his Master’s interest, and it shall be set up before sun and moon in the public view of the world.’ A Covenanting minister’s ordination! Secretly he got back to Scotland, and soon his name was linked with the very fragrant names of Cargill, Welwood and Hall. Donald Cargill, ‘blest singular Christian, faithful minister and martyr’; Henry Hall of Haugh-head, ‘worthy gentleman, martyr and partaker of Christ’s sufferings’; and ‘burdened and temperate John Welwood,’ who, seeing from his cold den his last dawn upon his native hills, said, ‘Welcome Eternal Light, no more night or darkness for me.’ The course of Richard Cameron was as swift and bright as that of a blazing meteor. He was fiercely hunted, but kindly housed, and although there was a huge price on his head, there was none that would betray him. Closely sought, he was ever sheltered; greatly loved, and that unto death, ever with his brother Michael by his side. His sermons were full of the warm welcoming love of the Lord Jesus Christ for poor helpless sinners: ‘Will ye take him? Tell us what ye say! These hills and mountains around us witness that we have offered him to ye this day. Angels are wondering at this offer. They stand beholding with admiration that our Lord is giving ye such an offer this day. They will go up to report at the Throne what is everyone’s choice.’ He preached memorably from such texts as these: Jeremiah 3:19, ‘How shall I put thee among the children?’; Matthew 11:28, ‘Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest’; Isaiah 32:2, ‘And a man shall be as an hiding place from the wind and a covert from the tempest’; Isaiah 49:24, ‘Shall the prey be taken from the mighty, or the lawful captive delivered?’; and John 5:40, ‘And ye will not come unto me, that ye might have life.’ In the midst of this sermon, seeking to make a contract between human hearts and Christ, he fell a-weeping, and crowds wept with him, their hearts tendering to the Man of Calvary. As was Cameron’s preaching, so was his praying, and his practising. Such as he believed what James Fraser, fellow-sufferer in the same cause, said ‘Of a Minister’s Work and Qualification’: ‘That which I was called to was to testify for God, to hold forth his name and ways to the dark world, and to deliver poor captives of Satan, and bring them to the glorious liberty of the children of God. This I was to make my only employment, to give myself to, and therein to be diligent, taking all occasions.’ And thus he goes on, clear in his apprehension as to the greatest calling on earth, and finishing so markedly, ‘And my own soul to lie at the stake to be forfeit if I failed; and this commission might have been discharged though I had never taken a text or preached formally.’ May we all be delivered from merely taking a text and preaching formally! Then came the magnificently brave Sanquhar Declaration, and the savagely intensified hunt of the men of blood. Less than three weeks before fierce Ayrsmoss, Richard Cameron said, ‘I shall be but a breakfast to the enemies shortly.’ After a day of prayer, twelve days from the end, his word was, ‘my body shall dung the wilderness within a fortnight.’ And ‘he seldom prayed in a family, or sought a blessing, or gave thanks, but he requested that he might wait with patience till the Lord’s time came.’ The last Sabbath of his life he spent with the dauntless veteran, Donald Cargill, and preached from Psalm 46.10, ‘Be still and know that I am God.’ The next Sabbath Cargill was preaching from the words, ‘Know ye not that there is a great man and prince fallen this day in Israel.’ It was a time of eating of the bread of affliction. The last week of Richard Cameron’s life was lived with about sixty others. Patrick Walker, the Covenanter Pedlar, the Covenanting John Bunyan, says of them in his unique record, ‘They were of one heart and soul, their company and converse being so edifying and sweet, and having no certain dwelling-place they stayed together, waiting for further light in that nonesuch juncture of time.’ They were somewhat armed, and about twenty of them had horses. Some may feel that they should not have taken up arms at all. Many Covenanters themselves felt like this, believing that there was a better testimony to be gained by suffering than by resisting. Their own outlawed ministers and writers counselled them to be ‘as jewels surrounded by the cutting irons’, and so, ‘to seal from your own experience the sweetness of suffering for Christ,’ since ‘there is an inherent glory in suffering for Christ’. Bur there were many others who, while they could go through much themselves, could not endure seeing others subjected to the utmost miseries and cruelties, and were as those when ‘every man had his sword upon his thigh’. Whatever we feel, we cannot but love them, these rebels so glorious, so brave for God. It was of them Delta Moir wrote:

We have no hearth—the ashes lie

In blackness where they brightly shone;

We have no home—the desert sky

Our covering, earth our couch alone;

We have no heritage—depriven

Of these, we ask not such on earth;

Our hearts are sealed; we seek in Heaven

For heritage, and home, and hearth.

O Salem, city of the Saints,

And holy men made perfect! we

Pant for thy gates, our spirits faint

Thy glorious golden streets to see;

To mark the rapture that inspires

The ransomed and redeemed by grace,

To listen to the seraph’s lyres

And meet the angels face to face.

The Lion of the Covenant spent his last night on earth at Meadowhead Farm, the home of William Mitchell. In the morning he washed his face and hands in an old stone trough. On drying himself, he looked at his hands and laying them on his face, he said to Mrs Mitchell and her daughter, ‘This is their last washing. I have need to make them clean, for there are many to see them.’ At this Mrs Mitchell wept. That day at about four in the afternoon, the dragoons came upon that Bible-reading band ‘in the very desert place of Ayrsmoss’. The Covenanters gathered around their young leader with the horsemen on either side of those on foot. He led them in prayer, appealing three times to the Lord of Sabaoth, to ‘spare the green, and take the ripe’. Looking on his younger brother, he said to him, ‘Come, Michael, let us fight it out to the last; for this is the day that I have longed for, to die fighting against our Lord’s avowed enemies; and this is the day that we shall get the crown.’ To his loved fellows he said, ‘Be encouraged, all of you, to fight it out valiantly, for all of you who fall this day I see heaven’s gates cast wide open to receive them.’ Then, ‘with eyes turned to heaven, in calm resignation they sang their last song to the God of salvation.’ The dragoons, emboldened by greater numbers and better arms, attacked at once. The wanderers, as was their wont, defended bravely, and David Hackston says, ‘The rest of us advanced fast on the enemy, being a strong body of horse coming hard on us; whereupon, when we were joined, our horse fired first, and wounded and killed some of them, both horse and foot. Our horse advanced to their faces, and we fired on each other; I being foremost after receiving their fire, and finding the horse behind me broken I then rode in amongst them, and went out at a side without any wrong or wound. I was pursued by several, with whom I fought a good space, sometimes they following me, and sometimes I following them.’ At last with a treacherous and unfair blow David Hackston was struck down, but, he says, ‘they gave us all testimony of being brave resolute men.’ Nine were slain ‘of that poor party that occasionally met at Ayrsmoss only for the hearing of the gospel’. Among them had flashed to God the dauntless spirit of him known among men as the Lion of the Covenant, Richard Cameron. And Michael, the inseparable, went with him. Most escaped into the wild wide mosses. Six prisoners only were taken. These were William Manuel, John Vallance, John Pollock, David Hackston, John Malcolm, and Archibald Alison. From the severity of his wounds and from the harsh treatment he received, William Manuel died as he was being carried into the Edinburgh Tolbooth. From the same causes John Vallance died the day following. John Pollock was most cruelly treated, but in the midst of it was steadfast and cheerful, and was banished as a slave to the American Plantations with the marks of his torture still upon him.

* * *

From whom did the early American slaves wrested from Africa hear the gospel? No doubt from Puritans and Quakers. But such were not fellow slaves. The former lived more in their own settlements, and the latter to their everlasting credit would not hold slaves. Whosoever got to a Quaker settlement was at once a free man. To the West Indies, Barbados and South Carolina many Covenanters were sent as slaves. The accounts of their tragic hell-ships make painful reading. Hundreds of these godly men and women, shipped to be sold as slaves, perished in most terrible conditions through disease, and in fearful storms were drowned miserably battened under hatches. From those who reached the Plantations black slaves heard the gospel, and thus white-skinned slave and black rejoiced in one common Lord. In our young years we were rightly familiar with Longfellow’s poem, beginning: Beside the ungathered rice he lay, His sickle in his hand, but it is possible that it was not always an African who so lay. Now and again it may have been one who in his last visions saw not himself as if ‘once more a king he strode’, but one who was back once again in fellowship among the hunted ‘of one heart and one soul’. The Negro Spirituals always have a hearing. The words of worship there united with the moving melody are a living union. But such melodies, it seems, may be sought for in vain in the negroes’ own native land, Africa. Whence came they? Out of something wondrously new, the dark soul meeting with the Light of Life, Christ Jesus? Yes! And out of fellowship in his sufferings, and the fellowship of Christ Jesus in the slaves’ sufferings. Yes, no doubt of that. But there are seeming traces of time and melody in these lovely spirituals which are reminiscent of the music of the old metrical Psalm-singing. Who can say? At any rate, these banished men and women carried the message of redeeming love to their fellow-slaves of another race.

* * *

The other three prisoners were executed, David Hackston being shockingly murdered upon the scaffold, and John Malcolm, and Archibald Alison were hanged. Said John Malcolm, ‘Let His Cause be your cause in weal and woe.

O noble Cause! O noble Work! O noble Heaven! O noble Christ that makes it to be Heaven! And He is the owner of the Work! . . . I lay down my life, not as an evildoer, but as a sufferer for Jesus Christ.’ Said Archibald Alison, ‘What think ye of Heaven and Glory that is at the back of the Cross? The hope of this makes me look upon pale death as a lovely messenger to me. I bless the Lord for my lot this day . . . Friends, give our Lord credit; He is aye good, but O! He is good in a day of trial, and He will be sweet company through the ages of Eternity.’ Of those who escaped from Ayrsmoss, ‘some wept that they died not that day, but,’ says Patrick Walker, ‘those eight who died on the spot with him went ripe and longing for that day and death.’ The dragoons dug a pit and tumbled the dead into it, after they had cut off the head and hands of Richard Cameron, and the head of John Fowler in mistake for that of Michael Cameron. These were put into a sack to take to the blood-thirsty Council in Edinburgh. In passing through Lanark, the dragoons asked Elizabeth Hope if she would like to buy some calves’ heads, and shaking the martyrs’ heads out of the bag, they ‘kicked them up and down the house like footballs’, so that the woman fainted.

On reaching Edinburgh, the dragoons put the heads upon halberts with the cry, ‘there are the heads of traitors, rebels!’ One who was there said that he ‘saw them take Mr Cameron’s head out of the sack; he knew it, being formerly his hearer—a man of fair complexion with his own hair, and his face very little altered, and they put a halbert in his blessed mouth out of which had proceeded many gracious words.’ Robert Murray, as he delivered them to the Council, said, ‘These are the head and hands that lived praying and preaching, and died praying and fighting.’ And those ghouls of gore paid over the price of the blood of one who died at about the age of his Master.

Before the hangman set head and hands on the bloodstained Netherbow Port, the fingers pointing grimly upwards on either side of the head, a hero saint lying in prison was shown them. He was Alan Cameron, Covenanter. The cruel question was asked him. ‘Do you know them?’ ‘His son’s head and hands which were very fair, being a man of fair complexion like himself.’ He kissed them saying, ‘I know them, I know them. They are my son’s, my own dear son’s. It is the Lord. Good is the will of the Lord, who cannot wrong me nor mine, but has made goodness and mercy to follow us all our days.’ A prisoner, head of a broken home, the father of martyred sons and daughter! It is the answer of the more-than-conqueror, the sufferer in Christ, full of faith and of the Holy Ghost; and having the heart full of the power and music of the Good Shepherd Psalm:

Goodness and mercy all my life

Shall surely follow me;

And in God’s house for evermore

My dwelling place shall be.

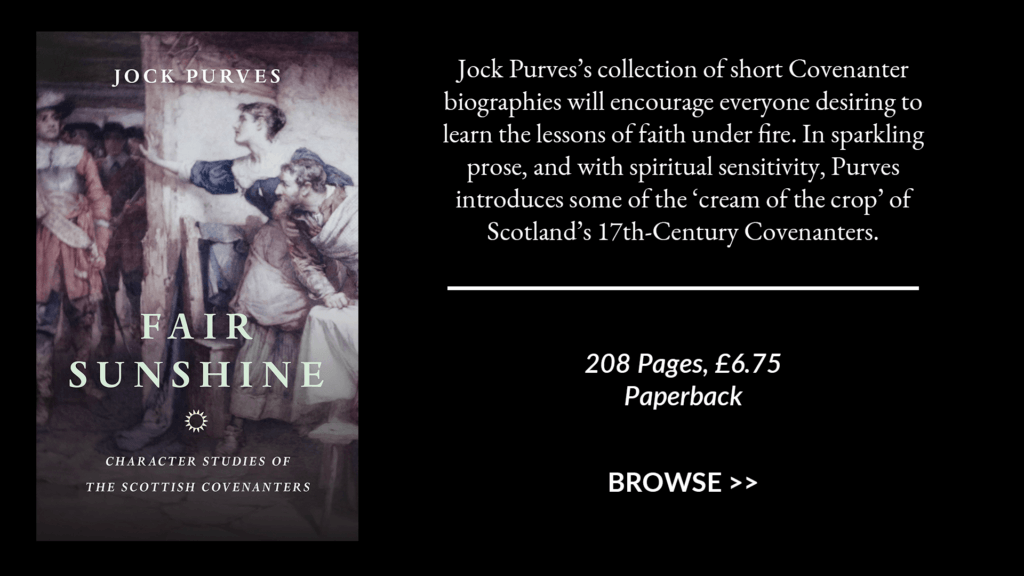

Featured Image: Alexander Peden at the grave of Richard Cameron, from Anderson’s Bass Rock. (Public Domain).

Latest Articles

Finished!: A Message for Easter March 28, 2024

Think about someone being selected and sent to do an especially difficult job. Some major crisis has arisen, or some massive problem needs to be tackled, and it requires the knowledge, the experience, the skill-set, the leadership that they so remarkably possess. It was like that with Jesus. Entrusted to him by God the Father […]

Every Christian a Publisher! February 27, 2024

The following article appeared in Issue 291 of the Banner Magazine, dated December 1987. ‘The Lord gave the word; great was the company of those that published it’ (Psalm 68.11) THE NEED FOR TRUTH I would like to speak to you today about the importance of the use of literature in the church, for evangelism, […]