John Newton on Handel’s Messiah

In 1985 the Banner of Truth published the 6 volume Works of John Newton. The most valuable volumes are those that contain the famous letters of Newton and the Olney Hymns. Volume IV consists of fifty sermons by Newton on the texts used by Handel in his oratorio ‘Messiah.’ Newton had an uncertain relationship with ‘Messiah’ and this is traced out by John M. Brentnall in an article in the current edition of ‘Our Inheritance’ the magazine of Protestants Today and used by permission. John M. Brentnall himself is a Derby pastor and the author of ‘Just a Talker’ Sayings of John ‘Rabbi’ Duncan which is also published by the Banner of Truth.

Handel’s oratorio ‘Messiah’ is perhaps the greatest musical masterpiece to have been composed in England. It is a measure of its greatness that each generation since Handel’s day has felt the desire to perform it. What is not generally known is that John Newton, converted slave-trader and author of Amazing Grace, preached fifty sermons from the texts of the oratorio to his congregation at St Mary Woolnoth, London.

By 1741, after almost thirty years of success in England, Handel was greatly in debt. On 8 April of that year he gave what he expected to be his farewell concert. Then two unforeseen events converged to change his whole life. A wealthy friend, Charles Jennings, gave Handel a libretto based on the person and work of Christ taken entirely from Holy Scripture. He also received a commission from a Dublin charity to compose a work for a benefit performance. The composer put the two together, and the oratorio was born.

Handel set to work on the twenty-second of August in his home in London, and became so absorbed in his new venture that he hardly stopped for food. Within six days Part One, containing Old Testament prophecies of Christ, Luke’s account of the angels and the shepherds, and a summary of Messiah’s mission, was completed. Nine days later he had finished Part Two, which deals with Christ’s sufferings and death. After only a further six days Part Three, setting forth the glory of Christ and the future hopes of his people, was concluded. Within two more days, Handel had orchestrated the whole work. In all, two hundred and sixty pages of manuscript had been filled in only twenty four days! Considering the work’s durability and the short time involved in its construction, it remains perhaps the greatest feat in the history of music. Later, as he groped for words to describe what he had experienced Handel told a friend, ‘Whether I was in the body or out of my body when I wrote it I know not.’ He gave the commissioned work the simple title Messiah and supervised its premiere on 13 April 1742, raising £400 for the charity. The following year Handel staged it in London in face of opposition from the Church of England.

John Newton’s Response

It was over forty years later that John Newton, now brought by God’s grace through many dangers, toils and snares, was stirred with concern for his parishioners by the centenary celebrations in Westminster Abbey of Handel’s birth. ‘Conversation in almost every company for some time past,’ he protested, ‘has much turned upon the commemoration of Handel; the grand musical entertainments, and particularly his oratorio of the Messiah, which have been repeatedly performed on that occasion in Westminster Abbey. If it could be reasonable hoped,’ he continued, ‘that the performers and the company assembled to hear the music were capable of entering into the spirit of the subject, I will readily allow that the Messiah, … might afford one of the highest and noblest gratifications of which we are capable in the present life. But,’ he concludes, ’till then, I apprehend that true Christians, without the assistance of either vocal or instrumental music, may find greater pleasure in a humble contemplation on the words of the Messiah than they can derive from the utmost efforts of musical genius.’ Newton’s disapproval of Handel’s work found expression in a series of sermons on its Biblical texts.

Picking no quarrel with the layout of the oratorio, Newton commends its arrangement as judicious, its passages as well-connected and its scope so comprehensive as to contain ‘all the principal truths of the gospel.’ Indeed, he summarises its main topics in a characteristically evangelical way.

The opening words of the oratorio are Isaiah’s comforting message to God’s sorrowful people ‘Comfort ye, comfort ye my people saith your God. Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem, and cry unto her, that her warfare is accomplished, that he iniquity is pardoned … The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in he desert a highway for our God’ (Isaiah 40:1-3). Newton entitles his sermon on this text ‘The Consolation’, noting that the eye of the prophet’s mind was fixed on an august person who would one day come and relieve his people of their misery. ‘He is directed to comfort the mourners in Zion with an assurance that this great event would fully compensate them for all their sorrows.’ ‘Speak to her heart,’ he paraphrases, ‘to her very case, and tell her that there is a balm for all her wounds, a cordial for all her griefs, in this one consideration–Messiah is at hand.’

Three Periods of Messianic Glory

When Messiah eventually came, men saw his glory, the glory as of the only-begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth. Newton understood the prediction, ‘and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed’ (Isaiah 11:5), to refer to three distinct periods. First, it refers to the personal appearance of Christ on earth in his incarnation. His glory then displayed several facets–‘He spoke with authority. He controlled the elements, he raised the dead. He knew and revealed and judged the thoughts of men’s hearts. He forgave sin, and thus exercised the rights and displayed the perfections of divine sovereignty in his own person.’ Second, it refers to the proclamation of his gospel throughout the world. ‘After his ascension,’ comments Newton ‘he filled his apostles and disciples with light and power, and sent them forth in all directions to proclaim his love and grace to a sinful world. Then the glory of the Lord was revealed, and spread from one kingdom to another people.’

Third, Newton clearly expected a millennial display of Christ’s glory. ‘We still wait for the full accomplishment of his promise, and expect a time when the whole earth shall be filled with his glory.’ Here then is a promise that should stimulate prayer for the worldwide spread the gospel.

Significantly Newton concludes his sermon on this text with a searching challenge: ‘Those of you who have heard the Messiah will do well to recollect whether you were affected by such thoughts as these while this passage was performed, or whether you were only captivated by the music.’ Let us test ourselves as we listen.

Because the blood of our Saviour had a retrospective efficacy it was the ground of comfort to all Old Testament saints. ‘Their noblest hopes,’ remarks Newton, ‘were founded upon the promise of Messiah; their sublimest songs were derived from the prospect of his advent. Isaiah therefore prepares this joyful song for the true servants of God who lived in his time. “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given, and the government shall he upon his shoulder; and his name shall he called Wonderful. Counsellor, The Mighty God, The Everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6-7). When a sinner is enlightened by the Holy Spirit to understand the character and offices of Messiah, his ability and willingness to save those who are ready to perish.. .then this song becomes his own, and exactly suits the emotions and gratitude of his heart.’

Entitled ‘Characters and Names of Messiah,’ Newton’s sermon on this text dwells lovingly on each name mentioned: ‘He is Wonderful in his person, obedience and sufferings; in his grace, government and glory… And he is our Counsellor or advocate with the Father who pleads our cause and manages all our affairs in perfect righteousness and with infallible success. He is the Mighty God. Only the mighty God could be a suitable Shepherd to lead millions of weak, helpless creatures to glory. Further, he shall be called the Everlasting Father, for his brethren are also his children… born into his family by the efficacy of his own Word and Spirit. Lastly he shall be called the Prince of Peace, whose sovereign prerogative it is to speak peace to his people, for he has made peace by the blood of his cross. Such is the character of Messiah. This is the God whom we adore, our almighty unchangeable Friend!’

Handel is also careful to emphasize these glorious titles. After light string figures introduce the voices to express believers, joy that the holy child Jesus is born for them, the music builds up to those huge block choral entries for which Handel is so famous. Each divine title is punctuated by an effective break, after which the two leading ideas, of the Son and his titles, wonderfully combine in a mass of rich and exhilarating choral tone.

The section dealing with the angel and the shepherds is introduced by the delightfully placid and Italianate Pastoral Symphony. With a few deft strokes Handel paints the whole scene in exquisite tones: a clear-voiced soprano or treble narrates the episode and enunciates the angel’s message while arpeggiated or fluttering violin figures suggest both the gathering excitement and the angel’s wings. The chorus ‘Glory To God’ is not one of Handel’s best, yet its word-painting is effective.

Newton was determined to dampen any enthusiasm for the oratorio. His remarks on these texts are quite resentful: ‘The gratification of the great, the wealthy and the gay was chiefly consulted in the late exhibitions in Westminster Abbey. But notwithstanding the expense of the preparations and the splendid appearance of the auditory, I may take it for granted that the shepherds who were honoured with the first information of the birth of Messiah enjoyed at free cost a much more sublime and delightful entertainment.’

The Effects of His Appearance

Our next extract deals sublimely with the effects of our Lord’s appearance on earth. The first text is Isaiah 35:5-6. ‘Then shall the eyes of the blind he opened and the ears of the deaf unstopped: then shall the lame man leap as an hart, and the tongue of the dumb shall sing.’ Physical blindness, Newton reminds us, is an emblem of the far more dreadful evil of spiritual blindness. Christ came, therefore, not merely to restore men’s eyesight, but especially to open their minds, unlock their wills and open their hearts, that their lips might show forth his praise.

The second text is Isaiah 40:11. ‘He shall feed his flock like a shepherd. he shall gather the lambs with his arm, and carry them in his bosom, and shall gently lead those that are with young.’ In his setting of these words Handel felicitously combines the tender promise of Isaiah with the gracious invitation of the Saviour, ‘Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy-laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn of me, for I am meek and lowly in heart, and ye shall find rest unto your souls’ (Matthew 11:28-29). Says Newton, ‘The sinner who is enlightened to know himself, his wants, enemies and dangers, will not dare to confide in anything short of an almighty arm: he needs a shepherd who is full of wisdom, full of care, full of power, and possessed of those incommunicable attributes of deity, omniscience and omnipresence. Such is our great Shepherd; and He is eminently the Good Shepherd also, for he laid down his life for the sheep and has redeemed them to God by his own blood.’

Concerning Christ’s invitation Newton adds, ‘But what is it to come to Christ? It is to believe in him, to apply to him, to make his invitation and promise our ground and warrant for putting our trust in him. Come therefore unto him; venture upon his gracious word, and you shall find rest for your souls.’

Our Saviour’s Sufferings

The central section of Handel’s oratorio deals with our Saviour’s sufferings. In the aria, ‘He was Despised’ the composer evokes a sense of deep grief through the simplest musical means–drooping violin figures with broken phrases in the vocal line. The text belongs to the great Suffering Servant passage in Isaiah 53. The prevailing thought is rejection: though Christ loved men, they despised him. ‘O for a realising impression of this his extreme humiliation and suffering, that we may be duly affected with a sense of his love to sinners, and of the evil of our sins, which rendered it necessary that the Surety should thus suffer.’

There are many fine passages in this central section, especially in this great fugal chorus, ‘He trusted in God’ and the widely-modulating recitative, ‘Thy Rebuke Hath Broken His Heart.’ We are not surprised to learn that when a friend visited Handel during his three weeks of self-imposed confinement he found him sobbing with intense emotion. The voluntary sufferings of our Saviour, under the Holy Spirit’s influence, will melt a heart of stone. By his death the Lord Jesus Christ overcame sin, death and Satan. Appropriately a whole section outlining the world-wide spread of the gospel now follows. This culminates in the splendid and exhilarating Hallelujah Chorus. The precedent set by the king at the oratorio’s first London performance–of standing as the triumphant opening notes rang out–was followed by the entire audience. It not only initiated a tradition observed to this day but also secured increased acceptance of Handel’s work. By the close of his long life Messiah had become firmly established in the standard choral repertory.

Once more Newton strikes a censorious but spiritually searching note: ‘The impression which the performance of this passage in the oratorio usually makes upon the audience is well known. But however great the power of music may be it cannot soften and change the hard heart, it cannot bend the obdurate will of man. If all the people who successively hear the Messiah, who are struck and astonished for the moment by this chorus in particular, were to bring away with them an abiding sense of the importance of the sentiment it contains, the nation would soon wear a new face. But do the professed lovers of sacred music in this enlightened age live as if they really believed that the Lord God omnipotent reigneth? I appeal to conscience; I appeal to fact.’

Whatever our personal response, the cumulative power of the setting of these glorious words certainly reminds the devout listener of the brightness of heaven where our Saviour reigns above all blessing and all praise.

The Second Coming of Christ

The third and final part of Handel’s masterpiece looks forward to our Lord’s Second Coming. Based on texts from 1 Corinthians 15, Romans 8, and Revelation 5, it is introduced by a striking and beautiful reference to Job. As the eagle eye of the patriarch’s faith and hope scans the centuries in eager anticipation of his own resurrection, he exults, ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand in the latter day upon the earth. And though after my skin worms destroy this body yet in my flesh shall I see God’ (Job 19:25-26). Newton grasps the salient points in this remarkable statement and applies them with warmth and clarity. ‘There is no name of the Messiah more significant, comprehensive or endearing,’ he claims, ‘than the name Redeemer.’ The Hebrew word for Redeemer, goel, primarily signifies a near kinsman, he with whom the right of redemption lay. Thus Messiah took upon him our nature, and by assuming our flesh and blood became nearly related to us, that he might redeem our forfeited inheritance, restore us to liberty and avenge our cause against Satan, the enemy and murderer of our souls. Job uses the language of appropriation. He says, My Redeemer, and all that we know or hear or speak of him will avail us but little unless we are really and personally interested in him as our Redeemer. But how shall I know that he is my Redeemer? Our names are not actually inserted in the Bible, but our characters are described there. He is the Redeemer of all who put their trust in him. As we listen to this aria and are reminded again of the certainty of death, let us place or renew our trust in the risen Messiah, for if we die in Christ we shall rise again in Christ and live with him for ever.

The oratorio culminates in a scene from heaven. Round Messiah’s throne stand hosts of redeemed sinners and holy angels. They ceaselessly re-iterate his praises. As they do so they are joined by all creation: ‘Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by his blood, to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory and blessing. Blessing and honour, glory and power be unto him that sitteth upon the throne, and unto the Lamb, for ever and ever, Amen’ (Revelation 5:12).

Fittingly Newton’s last three sermons are entitled The Song Of The Redeemed, The Choir of Angels and The Universal Chorus. His main theme is that since the great redemption wrought out by Messiah is suited to every case of every sinner from every nation, so when all the redeemed are gathered together in heaven they will constitute one family, united under one head; and since not one of them contributed a thing to their redemption they ascribe all glory to him. During the course of his exposition Newton expresses his desire that his hearers’ meditations on the Messiah would leave them with well-grounded hopes of meeting again soon around that self same throne, there to join the angels and the rest of the redeemed in singing the praise of God and the Lamb.

We would have preferred Newton to have ended there, but even with all heaven open before him he cannot resist a final strike at the very concept of the oratorio. ‘It is probable,’ he concludes, ‘that those of my hearers who admire this oratorio, and are often present when it is performed, may think me harsh and singular in my opinion that of all our musical compositions this is the most improper for a public entertainment.’ While it continues to be admired, he adds, ‘I can rate it no higher than as one of the many fashionable amusements which mark the character of this age of dissipation.. I am afraid it is no better than a profanation of the name and truths of God, a crucifying the Son of God afresh. You may judge for yourselves.’ As we listen to the acclamations of the crowned Redeemer and follow Handel as he piles up his harmonies in massive ranks, concluding the Amen in a blaze of majesty, let us heed Newton’s counsel and judge for ourselves.

More from Newton

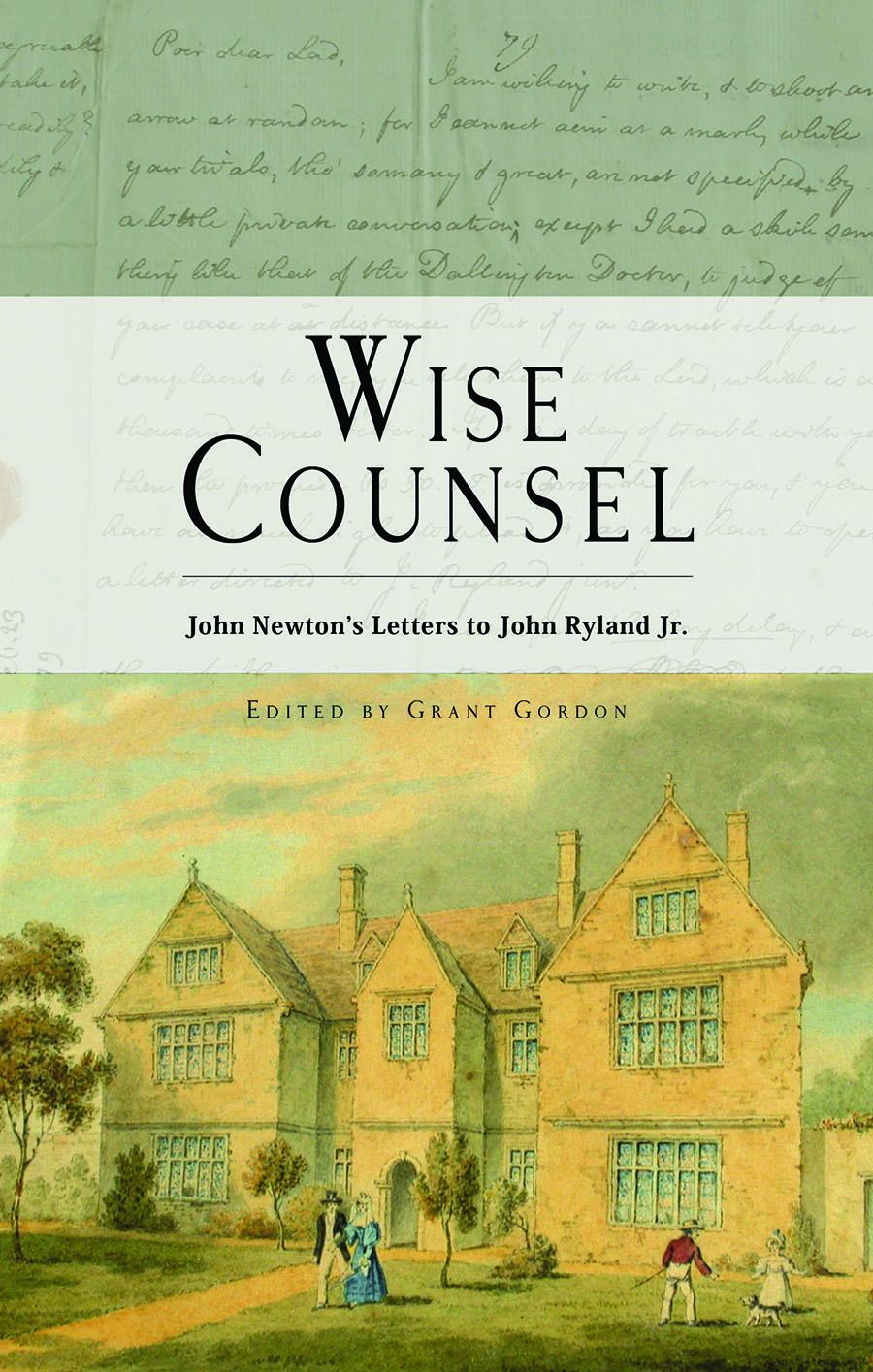

Wise Counsel

John Newton's Letters to John Ryland, Jr.

Description

In 1985 the Banner of Truth published the 6 volume Works of John Newton. The most valuable volumes are those that contain the famous letters of Newton and the Olney Hymns. Volume IV consists of fifty sermons by Newton on the texts used by Handel in his oratorio ‘Messiah.’ Newton had an uncertain relationship with […]

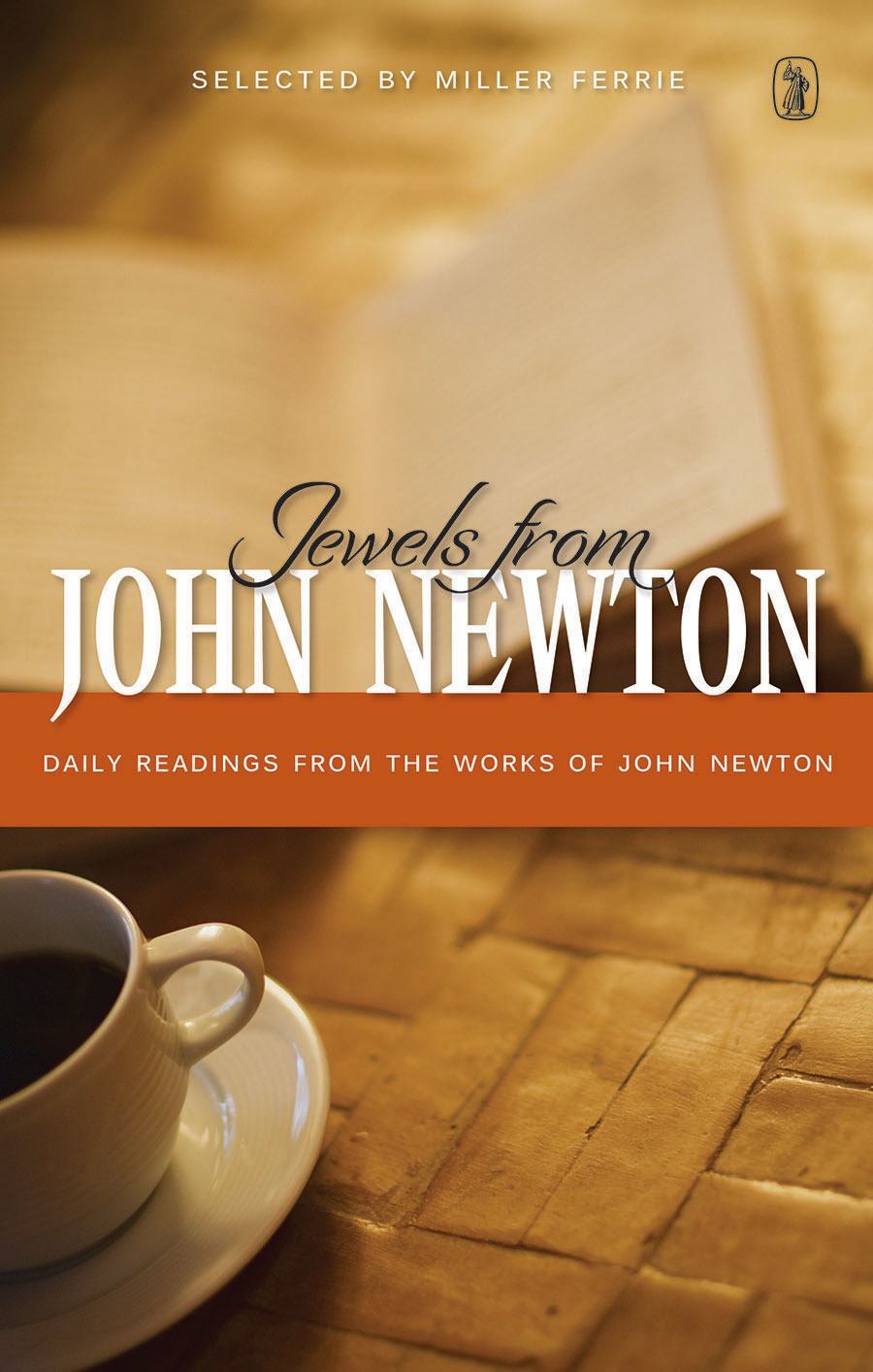

Jewels From John Newton

Daily Readings from the Works of John Newton

Description

In 1985 the Banner of Truth published the 6 volume Works of John Newton. The most valuable volumes are those that contain the famous letters of Newton and the Olney Hymns. Volume IV consists of fifty sermons by Newton on the texts used by Handel in his oratorio ‘Messiah.’ Newton had an uncertain relationship with […]

Description

In 1985 the Banner of Truth published the 6 volume Works of John Newton. The most valuable volumes are those that contain the famous letters of Newton and the Olney Hymns. Volume IV consists of fifty sermons by Newton on the texts used by Handel in his oratorio ‘Messiah.’ Newton had an uncertain relationship with […]

Latest Articles

Finished!: A Message for Easter 28 March 2024

Think about someone being selected and sent to do an especially difficult job. Some major crisis has arisen, or some massive problem needs to be tackled, and it requires the knowledge, the experience, the skill-set, the leadership that they so remarkably possess. It was like that with Jesus. Entrusted to him by God the Father […]

Every Christian a Publisher! 27 February 2024

The following article appeared in Issue 291 of the Banner Magazine, dated December 1987. ‘The Lord gave the word; great was the company of those that published it’ (Psalm 68.11) THE NEED FOR TRUTH I would like to speak to you today about the importance of the use of literature in the church, for evangelism, […]