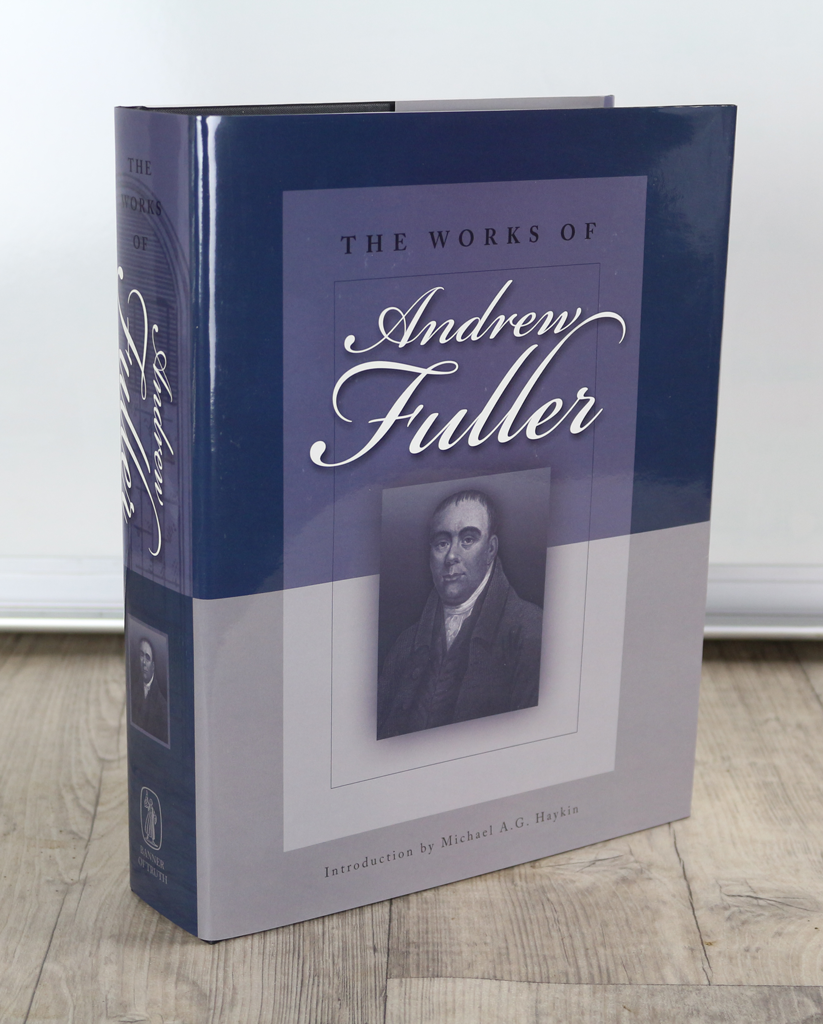

The Works of Andrew Fuller

Out of stock

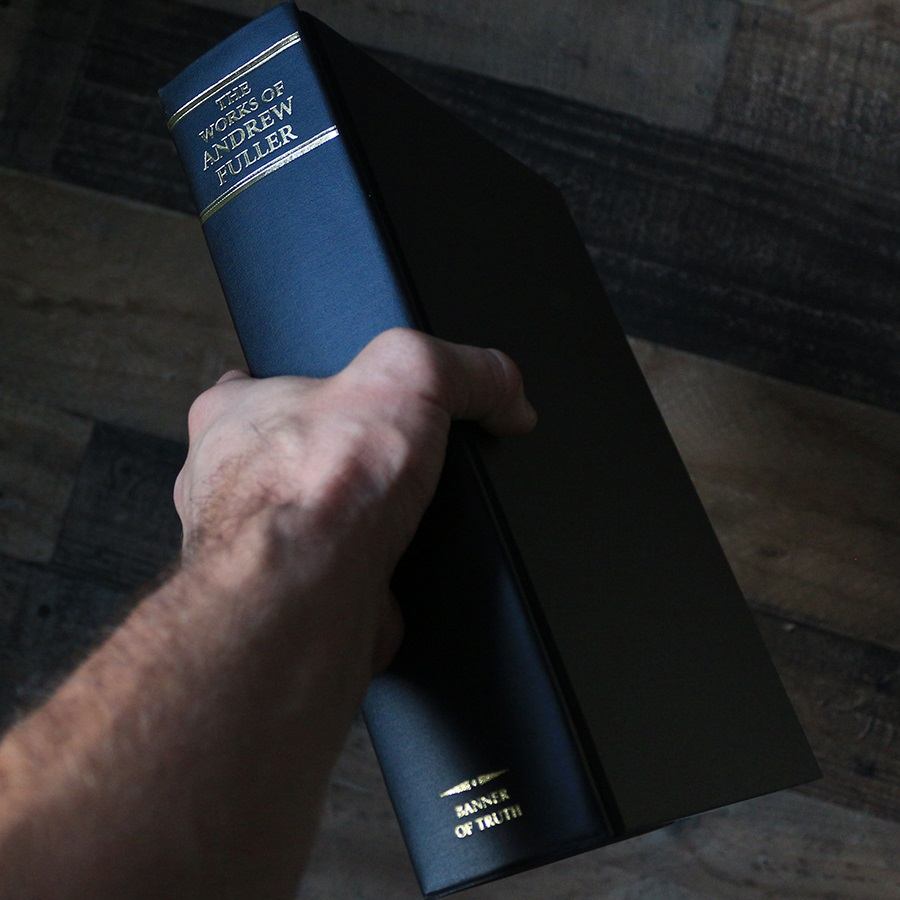

| Weight | 6.34 lbs |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 11.4 × 8.8 × 2.4 in |

| ISBN | 9780851519555 |

| Binding | Cloth-bound |

| Topic | General Theology, Pastoral Biography |

| Original Pub Date | 1841 |

| Banner Pub Date | Jun 1, 2007 |

| Page Count | 1012 |

| Scripture | Whole Bible |

| Format | Book |

Endorsements

‘Andrew Fuller was perhaps the most judicious and able theological writer that ever belonged to our denomination.’ — JOHN RYLAND JR.

‘The greatest theologian of his century.’ — C. H. SPURGEON

‘His influence on American Baptists was incalculable.’ — A. H. NEWMAN

‘Without a doubt, he was the greatest theologian of the late eighteenth-century transatlantic Baptist community.’ — MICHAEL A. G. HAYKIN

Book Description

Andrew Fuller (1754-1815), Baptist minister and theologian, was a truly outstanding man and one of the most attractive personalities in church history. Charles Haddon Spurgeon once described him as ‘the greatest theologian’ of his time, while his close friend, William Carey (1761-1834) expressed the thought of many who were personally acquainted with him, when he said, ‘I loved him.’

Converted in 1769, Fuller was called to the pastorate of his family’s church in Soham, Cambridgeshire (1775). These were the formative years of his ministry, when his theological understanding was sharpened through close study of the writings of Jonathan Edwards, and by his life-long friendships with his closest ministerial colleagues, Robert Hall Sr., John Ryland Jr., and John Sutcliff.

In 1782 Fuller became pastor of the Baptist church in Kettering, Northamptonshire. Here he spent 33 fruitful years in pastoral ministry, theological controversy, and missionary endeavour. Perhaps the most significant event in his ministry here was the publishing in 1785 (second edition 1801) of his The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation. Its main purpose was to set forth the truth that ‘faith in Christ is the duty of all men who hear, or have opportunity to hear, the gospel.’ ‘This epoch-making book’, says Michael Haykin, ‘sought to be faithful to the central emphases of historic Calvinism while at the same time attempting to leave preachers with no alternative but to drive home to their hearers the universal obligations of repentance and faith.’ Its significance cannot be exaggerated, for it led directly to Fuller’s whole hearted involvement in the formation of the Baptist Missionary Society (1792) and the subsequent sending of the society’s most famous missionary, William Carey to India (1793).

Fuller’s other major writings are also worthy of note. In The Calvinistic and Socinian Systems Examined and Compared, as to their Moral Tendency he combated the Socinianism of Joseph Priestley, (which denied the Trinity and the Deity of Christ); in The Gospel Its Own Witness Fuller countered the Deism of Thomas Paine (William Wilberforce, who admired Fuller as a theologian, considered this to be Fuller’s most important treatise); and in his Strictures on Sandemanianism Fuller defended the biblical doctrine of faith against those who held to an intellectualist view of saving faith, a ‘bare belief of the bare truth’.

The dominant theme of Fuller’s Works is ‘the grace of God in the gospel.’ In his last letter to his friend John Ryland, Jr., Fuller testified: ‘I have preached and written much against the abuse of the doctrine of grace, but that doctrine is all my salvation and all my desire. I have no other hope than from salvation by mere sovereign, efficacious grace through the atonement of my Lord and Saviour’.

Table of Contents Expand ↓

| MEMOIR | ||

| I | 1754 – 1776 Mr Fuller’s Birth… | xv |

| II | 1777 – 1783 Change in his Manner of Preaching… | xxvii |

| III | 1784 – 1792 Labours at Kettering… | xxxviii |

| IV | 1793 – 1814 Formation of Baptist Mission… | lvi |

| V | 1814, 1815 Journeys into various parts of England… | lxxxii |

| The Gospel Its Own Witness | 3 | |

| PART I | ||

| The Holy Nature Of The Christian Religion Contrasted With The Immorality Of Deism | 6 | |

| PART II | ||

| The Harmony Of The Christian Religion Considered As An Evidence Of Its Divinity | 28 | |

| CONCLUDING ADDRESSES | ||

| To Deists | 45 | |

| To The Jews | 47 | |

| To Christians | 49 | |

| The Calvinistic And Socinian Systems Examined And Compared As To Their Moral Tendency | 50 | |

| Socinianism Indefensible, Containing A Reply To Dr Toulmin And Mr Kentish | 110 | |

| Reflections On Mr Belsham’s Review Of Mr Wilberforce’s Treatise On Christianity | 131 | |

| Letters To Mr Vidler On Universal Salvation | 133 | |

| The Gospel Worthy Of All Acceptation | ||

| advertisement to the second edition | 150 | |

| PART I | ||

| The Subject Shown To Be Important, Stated, And Explained | 152 | |

| PART II | ||

| Arguments To Prove Faith In Christ To Be The Duty Of All Who Hear, Or Have Opportunity To Hear, The Gospel | 157 | |

| PART III | ||

| Objections Answered | 168 | |

| Concluding Reflections | 175 | |

| Appendix | 179 | |

| Defence Of The “Gospel Worthy Of All Acceptation,” In Reply To Mr Button And Philanthropos | 191 | |

| The Reality And Efficacy Of Divine Grace, By Agnostos | 234 | |

| Strictures On Sandemanianism, In Twelve Letters To A Friend | 256 | |

| Dialogues And Letters Between Crispus And Gaius | 294 | |

| Conversations Between Peter, James, And John | 309 | |

| Letters on the controversy with the rev a booth | 317 | |

| Letters Relative To Mr Martin’s Publication On The Duty Of Faith In Christ | 325 | |

| Antinomianism Contrasted With The Religion Of The Holy Scriptures | 334 | |

| Exposition Of Passages Relating To The Conversion Of The Jews | 497 | |

| Exposition Of Certain Prophecies Relating To The Millennium | 503 | |

| Exposition Of Those Scriptures Which Refer To The Unpardonable Sin | 505 | |

| Expository Notes On Various Passages | 507 | |

| Exposition Of Passages Apparently Contradictory | 529 | |

| Sermons And Sketches | 538 | |

| Circular Letters | 714 | |

| Letters On Systematic Divinity | 740 | |

| Thoughts On Preaching | 752 | |

| Memoirs Of The Rev Samuel Pearce | 760 | |

| An Apology For The Late Christian Missions To India, In Three Parts, With An Appendix | 796 | |

| Essays, Letters, On Ecclesiastical Polity | 829 | |

| Miscellaneous tracts, essays, letters, | 863 | |

| Reviews | 962 | |

| Answers To Queries | 971 | |

| Fugitive Pieces | 984 |

Related podcast episode

Related products

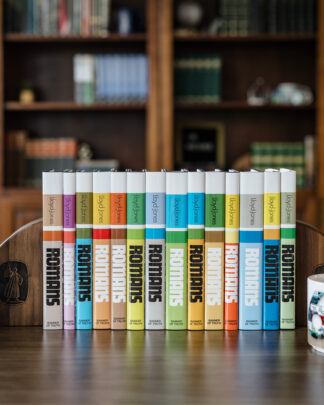

Romans

14 Volume Set

Description

This one-volume edition of Fuller’s Works contains a vast array of riches, including the epoch-making The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation. 1120pp.

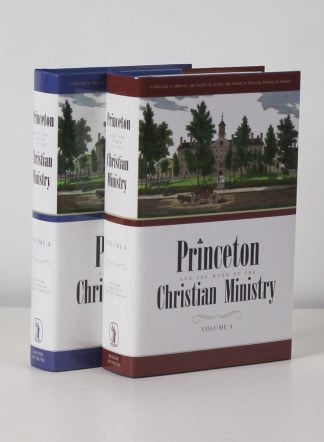

Princeton and the Work of the Christian Ministry

2 Volume Set: A Collection of Addresses and Articles by Faculty and Friends of Princeton Theological Seminary

Description

This one-volume edition of Fuller’s Works contains a vast array of riches, including the epoch-making The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation. 1120pp.

Majesty in Misery

3 Volume Set

Description

This one-volume edition of Fuller’s Works contains a vast array of riches, including the epoch-making The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation. 1120pp.

Joe Connolly –

Andrew Fuller said: “A persuasion of Christ being both able and willing to save all them that come unto God by him, and consequently to save us, if we so apply, is very different, from a persuasion that we are the children of God, and interested in the blessings of the gospel.” It is the “if we so apply” part that this Christian finds troubling: Does my salvation rest on my ‘applying’ to God for it? The Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ tells me that Christ determined to save those whom He loved from all eternity, even though they did not ‘apply’ to Him to do so! We are made willing in the day of His power – we do not make Him willing by ‘applying’. Christ is mighty to save, and He has performed the work for His blood-bought people. Fuller’s theology is inconsistent, and seems to be an apology for the doctrine of particular election and reprobation, as though he were ashamed of these truths.

David J Bissett –

Andrew Fuller was a dynamic theological, writing and pastor/preacher. I have this huge volume (one of the biggest books I own), and every time I read Andrew Fuller I am refreshed. There is a vividness to his style and a passion in his writings. Highly recommended.

Richard C Ross –

It’s claimed Andrew Fuller was ‘without a doubt, the greatest theologian of the late eighteenth-century transatlantic Baptist community.’ That’s a very narrow field – and an odd way of categorising theologians: do you set up those criteria before lifting a volume off the shelf! William Carey’s testimony says far more: ‘I loved him’.

This ranking of Fuller (a horrid practice) must be weighed. His Works (the book is enormous, heavy reading!) include a piece on the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the foundational doctrine of all doctrines. Sadly, this contribution is insignificant, not the work of a great theologian. It is little more than a laborious statement of the deity and person-hood of the three Persons of the Godhead. A task satisfactorily achieved thirteen hundred years earlier. Fuller fixates on ‘proof texts’, which prove little (repeating Bible texts is the preferred method of heretics). (No!) There’s nothing here approaching the sublimity of the meditations of John Owen, Thomas Goodwin, Thomas Boston and Jonathan Edwards – let alone the ‘early church Fathers’.

The ‘Antinomian’ piece, a characterising subject for Fuller, is a strange item, in more than one respect. Fuller is scathing of ‘antinomians’; expressing himself in stinging allegations, but leaves his ‘targets’ largely anonymous. This throws the ink of suspicion, of the most ungodly attitudes and practices, on all who, often unfairly, are treated to the emotive label of ‘Antinomian’. It’s often assumed that John Gill and William Gadsby, etc. were the subjects of Fuller’s lashings. How great an injustice that would be!

It’s easy to understand why William Carey would say, ‘I loved him’; but I’m far from convinced that Fuller deserves to be ranked (if this is to be done) alongside the names of those who, to most visitors to this website, will be the obvious candidates for such elevated regard. Sadly, we Baptists have produced far too few (any at all?) who could, in any century, be hailed as ‘the greatest theologian’. I wonder why that is.

Richard C Ross –

Fuller, in disagreement, states antinomianism ‘conceives the imputation of Christ’s righteousness as that by which we are not only treated as righteous but are actually without spot in the sight of God’. He alleges an ‘antinomian’ position implies the impossible: God ‘thinking a character to be different from what he really is’; that if a man believes ‘justification includes full remission of the justified man’s sins’ that man will conclude ‘he needs not daily to pray for forgiveness’. All this on ‘the doctrine of a standing or falling church’. [344] I suggest Fuller’s objections are erroneous.

The question is: what is ‘really’? Am I ‘treated’ as or am I ‘actually’ righteous ‘in the sight of God’? Does God ‘think’ of me differently from what I ‘actually’ am ‘in his sight’? The case is the believer is united to Christ, by insition, implantation: one with him, on the instant faith is placed in him. That is ‘really’! On that basis, I’m ‘treated’ as righteous because, being in Christ, I am objectively, passively and definitively ‘actually’ (‘existing in fact’) righteous; ‘without spot’, as he is without spot. That is my justification, on the basis of my union with Christ as ‘in fact’ my replete sanctification. Do I still need to ask for forgiveness daily? Emphatically, yes! How so? Well, because there’s a distinction to be made Fuller ignores: between ‘actual’ progressive sanctification and ‘actual’ definitive, replete sanctification. My eternal standing is secure in Christ; I have ‘in fact’ been definitively, irreversibly, irrevocably, immutably, as justice demands, declared, ‘in God’s sight’, objectively innocent of all guilt and in Christ as ‘actually’ righteous as Christ; for, through my union with him, he is my righteousness; personally ‘in fact’ my definitive, objective, replete sanctification. Subjectively and actively my daily performance, as a person secure in Christ, falls far below what I would wish it to be, strive, in gratitude, to please him as I might; and infinitely far below what he would wish it to be; my progressive sanctification is threadbare. ‘Wretched man that I am! There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.’